Drafted into the United States Army and sent to France, Earl R. Burnett of Texas fought in the final months of World War I and survived to witness the Armistice from the frontline trenches.

World War I is almost totally unknown to most Americans. We are hardly taught anything about it in school – I think my high school history classes spent less than a half-hour on the subject. Despite never being taught much about the war in school, I have always had a fascination with it. As I was turning 12, I stumbled upon the George Lucas television series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. Most of the episodes surrounded World War I, with a completely fictional Indiana Jones witnessing and taking part in real events. What I saw captivated me. Growing up in the infancy of the Internet, I had to still look for old books in the dusty and neglected sections of libraries as well as used bookstores in order to learn more. Over time, I began to amass quite a bit of knowledge and what was once a hobby has turned into a professional pursuit. Through my courses in politics and history, I have been able to research, teach, and continually read about it. One day it hit me that I might even have a relative who served Over There. What I found astonished me.

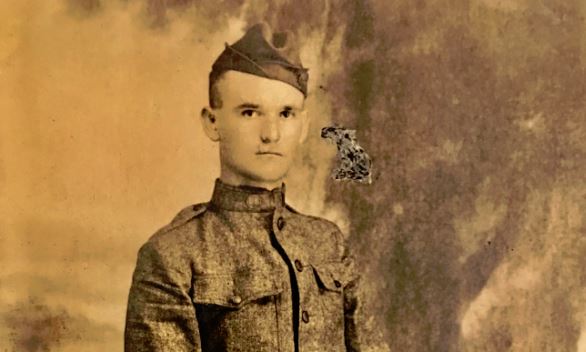

I asked my father if any of our Burnett relatives had served in the war. He replied that there was always a rumor that his uncle, my great grand-uncle, Earl R. Burnett, had served. I asked all of my living family for more information, but no one had any idea if, or where, he had served. If he had been there, I knew he had certainly survived the war since everyone in the family knew him as an older man. As the 100th anniversary of The Great War began in 2014, I decided to look into the rumor – but had no place to start. Over lunch one day, colleague of mine (and former US Air Force intelligence officer) at the small Virginia college where I teach told me to give me all of the information I had on my relative. A few minutes later, he produced a draft card with just enough information to start me on my search.

Although I found quite a lot on him, I have found that much of exactly what Earl did has been lost to history. I know the company he was in (the smallest administrative grouping available) but his, and almost all, of the US Army personnel records and files from World War I were burned in an archives fire in 1973. Hoping that Earl’s record might have survived, I sent in an application to search out his record. Unfortunately, the only thing that remains of his personnel file is a slip of paper he signed to receive his final paycheck upon discharge. The resulting story of his service has been pieced together through archival research at the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland; the US Army War College Archives in Carlisle, Pennsylvania; and various official Division histories, maps, and firsthand accounts of the company in battle in online archives. His name appears on the scant roll sheets which have survived in the National Archives. Aside from reading a myriad of books on the war, I was also able to visit the battlefields and villages in France, which gave me a completely new perspective on what he went through. It is impossible to know what he did and exactly where he was at any given moment, I can place him within a company’s actions with certainty.

It has taken over two years, four states, three countries, countless books, and many, many late nights, but I have finally been able to piece together the story of Earl R. Burnett in the war. The biggest shock to me, was that I found out he had witnessed the Armistice while on the front lines. His story is similar to many of the Doughboys who fought in the war, but not many of them were able to witness the end of the war on the battlefield.

Drafted, “Trained,” and Shipped to France

Earl was the youngest of six siblings and was raised on a small farm outside of the little town of Greenville, Texas. The war began when he was 19, but the United States didn’t enter the war for another three years. After a declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare by Kaiser Wilhelm II (which would target American ships), the US declared war on Germany in 1917. An isolationist country, the US had less than 200,000 soldiers, sailors, and Marines in active service. In order to overcome the numbers problem, the US instituted a draft in May 1917 to enlist enough men to fight. Earl was one of the first to be chosen and he was inducted into an infantry regiment in the US Army in Texas in April 1918. As America was totally unprepared for the realities of a modern war, the recruits received very little training – and without the actual weapons, gas masks, or artillery they would have to use in battle. Their training records note that almost nothing was available and they were “trained” by watching demonstrations and were tolf to pick up as much as they could. Although they were poorly trained, they set off in a hurry to France.

Earl arrived with his division in France in August 1918 (perhaps this was a homecoming of sorts, as one theory of the Burnett Family has it originating in France before settling in Scotland). Historian Edward G. Lengel writes that French civilians “swarmed the docks as American troopships entered port, waving caps and calling Doughboys saviors.” Many cried out to the disembarking troops, “Vive l’Amerique! Vive les Americains!” Children and young women followed the soldiers throughout the town and would sell fruit, “detestable postcards,” and wine and cognac when they stopped to rest. The boys didn’t get to rest for long and Earl and his division were shipped out for more training near the Front.

During the summer of 1918, preceding the arrival of the 7th Division, American commander General John J. “Blackjack” Pershing’s American troops had acquitted themselves admirably, halting the Ludendorff Offensive at the Battles of Belleau Wood (which kept Paris out of reach of Germany) and Chateau-Thierry. In August 1918, the commander of allied forces, French General Ferdinand Foch, insisted the American Army fight under French command in order to fit into his overall plan. Pershing refused and furiously argued with Foch over the subject. The two almost refused to work together until on September 2nd Foch compromised with Pershing, allowing for the American troops to take part in the plan under their own commanders. The plan for the American Army and Marines was broken down into three phases. Phase I would be to clear the Germans from the St. Mihiel salient that the Germans had held since 1914. Phase II was to recapture the Meuse-Argonne Forest and the German-held town of Sedan. Phase III would have the Americans push northeast from St. Mihiel towards the German-held medieval fortress town of Metz. The town was a stronghold of the German Army and it was the site of a vital railway hub the Germans had been using since 1914 to transport men and materiel up and down the Western Front. The official division history noted, after seeing the defenses at the end of the war, that the American Army would have paid an immense price to take Metz. Official reports after the war note that it most assuredly would have resulted in enormous amounts of casualties and, most likely, failure.

On September 12th, Phase I was carried out with combined American and French forces taking the town of St. Mihiel. On September 26th, Phase II of the plan was launched in the Meuse-Argonne Forest. What was initially supposed to take 2-3 weeks ended up taking twice that long (47 days) and cost 122,000 casualties, including 26,277 dead. During the battle, the First Army inflicted over 100,000 German casualties, and took 26,000 prisoners. The fighting was as intense and brutal as anything seen in the war and it was compounded by the inexperience of the US soldiers and commanders. In fact, the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne is still the single costliest battle Americans have ever fought overseas, eclipsing even Normandy, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

While the Battle of Meuse-Argonne was raging, Earl’s regiment was in a mandatory four weeks of training in preparation to move into the front lines. It was here that the men received their first gas masks, steel helmets, automatic weapons, and other implements they would be using at the Front. After four weeks of training, the regiment was shipped out to the Lorraine Sector of the Western Front near St. Mihiel to begin the push on Metz. The troops were brought by rail to a hub station and were required to march for 27 miles through a cold, rainy, and muddy October night and morning weighed down by all of their weapons and gear. The day before they were to move into support position at the Front, the regiment received their Browning Automatic Rifles (BARs) that they would be using. These were the first automatic rifles Americans would use in combat. They were given “intensive training” on their use for one whole day. On the night of October 9th, the regiment took their place in the reserve trenches in the wooded Fond-des-Quatre-Vaux ravine. Official division records describe what they experienced upon arrival:

“Contrary to expectations, the front line here was…no line at all, not even a trench, but merely a series of fox holes and other ineffective places of concealment and shelter….The German lines on this front were one to three hundred yards distant and the terrain was covered with a dense undergrowth of brush and trees. An extremely steep-banked ravine ran approximately though No Man’s Land between the two lines.”

It was also an extremely rainy season, and as the official record notes, “Rain and mud and more mud were the rule.”

In the Trenches

Five minutes after the Earl and his regiment took their position, one private was shot dead by a German sniper. The Americans were finding out that the sector, which had been in German hands since 1914, had been fortified immensely. The German Army had mapped out artillery coordinates for every inch of ground, had built up an extensive and elaborate trench system complete with enfilading fire from multiple positions, and had set tripwires and booby-traps for miles leading up to Metz. It was some of the best-built and defended terrain of the war.

The German aerial and artillery supremacy was especially pronounced in the area, and the Germans fired an average of 720 shells of all varieties per day each day in October. German airplanes and observation balloons constantly harassed the Americans night and day with no answer from the allies – the American planes had not yet arrived in the sector. On the night of October 11th, German shells began to saturate the area where Earl and the regiment was and they were ordered to keep their new gas masks on all night as the number of gas shells kept increasing. On the afternoon of the 12th, the Germans began to increase their artillery attacks all along the line and by midnight, had fired 4,000 shells, 2,100 of them were lethal gas.

The forest and ravine were so dense with growth and brush that the Americans could not find the enemy emplacements. On October 14th, the regiment sent out patrols to find out where the enemy was located, but failed to make contact, and no one was able to find the exact location of the German trenches. The official record notes that patrols often stopped short because they had no idea where the Front was. As the regiment continued to send out patrols, they were continually pushed back by well-hidden machine gun and sniper placements throughout the thick forest.

The best the patrols could manage was to quickly drive in stakes so that they could identify where a machine gun nest or enemy placement was located. While the stakes were being driven in, the Germans were secretly watching and sighting in their artillery on the stakes. When nightfall came, American patrols selected from the regiment were ordered to move up to the stakes and fire on the German position. However, the Germans were ready and would wait until the patrols were in position and then initiate a devastating artillery barrage, cutting the Americans to pieces and forcing those who survived back into hiding.

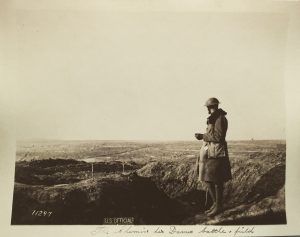

As the regiment sent out patrols, “heavy wire entanglements which were laced in among the trees and bushes and which they were unable to get through without detection” continually stopped al progress. I have walked directly through the ravine and woods Earl and his regiment were in, and I was truly shocked at how thick and impassable the growth really was. The trees are as thick as any forest I’ve ever been in, and the undergrowth is made up of vines and brambles that pull one back as one tries to move forward. Add to this a very steep 900-ft (300 m) hill (more like a cliff) as well as the entire wet, muddy, and decaying soil, and you begin to get a sense of what they were dealing with. Despite all of this, the regiment was able to slowly advance towards the summit of two hills: Hill 310 and Hill 323 both near the town of Rembercourt-sur-Mad.

On October 17th, the men tried to push up Hill 323, but found barbed wire entanglements interwoven and hidden in the trees with enfilading fire on the slope which drove them back. On October 19th, Earl and his Company were moved up further to the support trenches. On October 21st, the Germans began attacking the regiments using a coordinated assault of airplanes, artillery, and infantry (including shock troops). Over 350 bombs were dropped from unopposed German airplanes directly on the regiment. After an unrelenting artillery bombardment, the German infantry, suddenly attacked the regiment, forcing it back. After what the official records note as “severe fighting,” the Germans were finally

repulsed and sent back to their own trenches. Minor skirmishes and bombardments occurred constantly for the next several days and nights.

On October 30th and 31st, the Germans began to even more heavily shell the entire division, including over 1,000 mustard and phosgene gas shells, causing almost 100 casualties. The Americans, short on sleep, food, and ammunition must’ve felt as though they were on their last legs. They hadn’t had any rest since the beginning of October. The Germans flew airplanes overhead constantly and began to drop propaganda leaflets on the soldiers to try and convince them to stop fighting. It didn’t work. On November 1st, the regiment finally took Hill 323 and repulsed wave after wave of determined German counterattacks for the space of 30 straight hours. The next day, November 2nd, the regiment was finally ordered away from the Front to rest. However, the only way back was to return through the forest and ravine – over 18 dense miles – and it took several days for the regiment to reach their camp behind the lines. By the time they did, they were feeling the effects of having very little food, water, and rest for almost a month. The men were utterly exhausted.

Interestingly enough, on November 3rd, a Private William D. Burnett, who was in the same regiment and company as Earl, died of wounds he received from artillery fire on the front lines the previous month. I have not been able to find out much about him except that he was from Oklahoma and not immediately related to Earl.

Back on November 1st, word had come from Headquarters that ground was being gained in the Meuse-Argonne, and that the German Army was beginning to withdraw – most likely to buy time so they could set up a defensive position behind the Hindenburg Line (a deadly series of interwoven trenches set up as the last impassible defense of Germany). Pershing and Foch agreed that if the enemy was seen retreating, the Americans should pursue with haste in order to keep them from establishing a foothold. In the north, the Germans were falling back towards the town of Sedan. In the Lorraine Sector, where Earl and his regiment were, the Germans were falling back and “would probably pivot upon [the city of] Metz, holding the outer defenses 10 or 12 kilometers from the center of the city.” In such a scenario, the entire division would push the Germans and continually keep close contact. On November 4th, the Austrian Army surrendered to the allies and Germany began to stiffen its defenses. As such, the German Army fought with ferocity because their backs were against the wall.

November 11th, 1918

A new plan was put into effect by the allies on November 8th. The new plan required several American regiments to push through hilly and wooded terrain between the River Mad and the Bois-du-Trou-de-la-Haie. The area was chock full of German emplacements and traps, which had been tested and refined for years. Earl and his regiment were ordered to cut their rest short and hike back to the Front. The regiment was to be in place on the front line by the morning of November 10th to prepare for battle the next day. The regiment began the hike, but due to confusion and the inability to find their lines in the dark, the soldiers were far from their assigned positions the next morning. After a quick march, the regiment was finally able to get into place on the crest of Hill 323 after dark on November 10th.

November 11th was slated for the beginning of the attack on the German-held town of Rembercourt-sur-Mad and the hill behind it. The attack was to be preceded by a 3-hour bombardment at 8 am to reduce defenses and cut the barbed wire (which hardly, if ever, worked). Earl stood with his regiment in a frigid, wet, and muddy trench that morning on Hill 323 waiting for the order to go over the top.

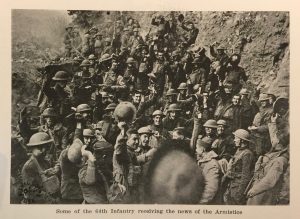

At 7:40 am, word was suddenly passed to the regiment that an armistice had been signed and all fighting would cease at 11 am. Rumors and false reports of an armistice had been swirling for weeks which caused many to not believe it. Taking no chances, the regiment was ordered to stay ready. Up and down the Western Front, the artillery on both sides began to escalate at a furious pace until the final hour. An American soldier nearby wrote, “Every Boche [German] gun between Donnmartin and Metz inclusive opened up on us. My God, how they strafed us. Everything from minenwerfers to 210s descended upon those woods. The soft ground billowed like the ocean.” The ground was wet and muddy, however, which absorbed much of the impact of the shells. An official report notes, “And so the Great War came to us heralded by a last, furious burst of artillery fire from both sides.”

At 11 am, firing completely ceased all along the front. An American soldier wrote, “the roar [of the artillery] stopped like a motor car hitting a wall.” He continued, “The resulting quiet was uncanny.” As the silence grew, Germans began to slowly emerge from their trenches, eventually climbing on parapets and shouting wildly. An American soldier watched the German soldiers as they “threw their hats, bandoleers, bayonets and trench knives towards us. They began to sing. Came one bewhiskered Hun with a concertina and he began goose-stepping along the parapet followed in close file by fifty others – all goose-stepping.” The Germans tried to fraternize with the Americans “in hopes of a hot meal or a good smoke.” The service newspaper Stars and Stripes wrote the following:

“The skyline of the crest ahead of them grew suddenly populous with dancing soldiers and down the slope, all the way to the barbed wire, straight for the Americans, came the German troops. They came with outstretched hands, ear-to-ear grins and souvenirs to swap for cigarettes….They came to tell how glad they were [that] the fight had stopped, how glad they were [that] the Kaiser had departed for parts unknown, how fine it was to know that they would have a republic in Germany at last.”

Orders were given forbidding fraternization in case the cease-fire was called off and to continue to hold the line. Temptation was too great for some of the Doughboys however, and a few ran out to exchange souvenirs. One American wrote,

“A big Yank named Carter ran out into No Man’s Land and planted the Stars and Stripes on a signal pole in the lip of a shell hole. Keasby, a bugler, got out in front and began playing ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ on a German trumpet he had found in Thiancourt. And they sang – Gee, how they sang!”

Not everyone took part in the celebration and most of the attempts at fraternization by the Germans “was at once stopped in the attempt.”

All night long the Germans celebrated behind their lines, sending up “pyrotechnics of different descriptions.” The night was completely lit up by the display. In the valley below where Earl stood in his trench “came the sound of Boche songs and revelry interspersed with bugle calls.” The Americans were ordered to remain in the trench all night until further orders. Earl witnessed one of the most incredible events in history firsthand standing in a trench overlooking No Man’s Land.

In the days following the Armistice, the regiment was pulled back into the small villages and towns along the Front and began to help rebuild them. Earl and his company were housed in the village of Domevre in wooden and stone structures – which was quite a change from the muddy foxholes they had been in the past several months. A few days after relocating to Domevre, Earl and his regiment watched in amazement as streams of ragged and emaciated prisoners of war walked back from the German lines. At first, only French prisoners came through the town – and then, amazingly, Russian prisoners followed them. The Russian soldiers had been placed on the line on Western Front as part of a good faith ally program between France and Russia in 1916. When they were allowed to return, they found their country in a desperate civil war. Some went back home, others stayed and made their homes in France. They were fed, clothed, and taken care of for 24 hours before being put on a train and shipped home. The Americans moved once more across France and headed back to America in June 1919.

Earl returned home, was discharged, married, and went to work for the Texas Department of Transportation shortly after the war. According to his daughter, he never said much about the war. He sometimes shared funny stories and songs he learned in France with his nieces and nephews, and some of them received little mementos he had picked up in France. He was, according to everyone who knew him, a very kind and funny man, who was always worked hard, was active in his church, but always loved to have fun when it was time. By all counts, he lived a happy and healthy life. He died surrounded by his loved ones in 1977.

November 11th, 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the Armistice ending World War I. It saved countless soldiers’ lives, including Earl and his company that morning. Had he been sent into battle, there was a high probability that he would not have survived. Earl was a Burnett who lived up to honor of the name in both war and peace, and was lucky enough to witness one of the most important events in world history firsthand. As we remember those who took part in The Great War this very special November 11th, may we also remember those Burnetts who fought – and especially those who didn’t make it back.

Guy F. Burnett, PhD

Hampden-Sydney College